Pressure capabilities represent one of the most critical specifications when selecting and operating pinch valves. Unlike traditional metal-bodied valves, pinch valves rely on flexible elastomer sleeves that respond differently to internal pressure, vacuum conditions, and external compression forces. Understanding pinch valve pressure ratings, limitations, and operational considerations ensures safe, reliable performance while maximizing valve service life. This comprehensive guide examines all aspects of pinch valve pressure performance, from basic ratings to advanced application scenarios.

Understanding Pinch Valve Pressure Ratings

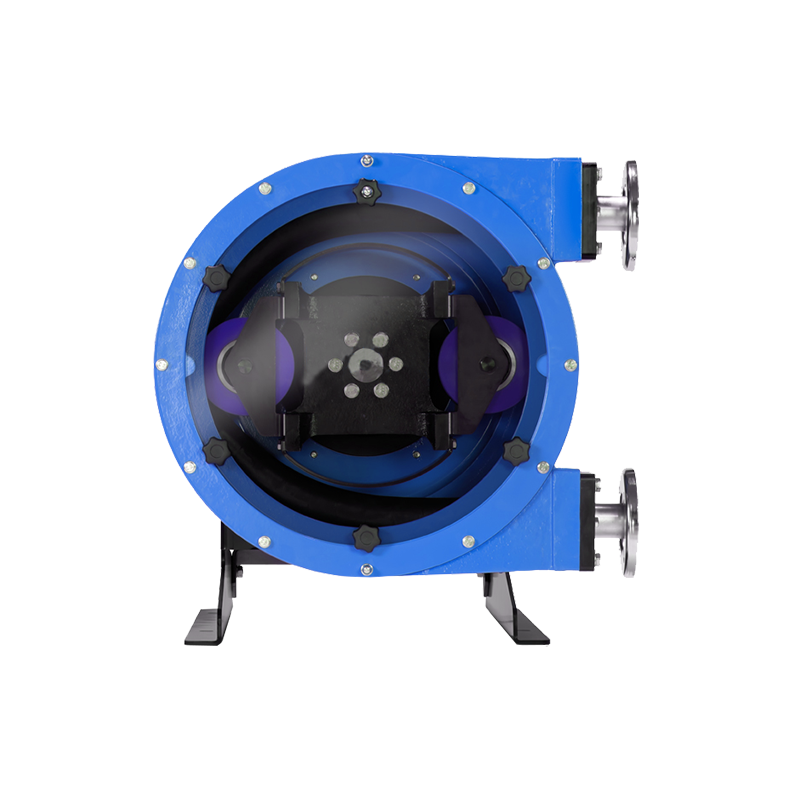

Pinch valve pressure ratings differ fundamentally from conventional valve ratings due to the unique operating principle. A pinch valve controls flow by compressing a flexible sleeve, meaning the pressure rating depends on the sleeve's ability to withstand both internal fluid pressure and external pinching force simultaneously. This dual-stress condition creates more complex pressure limitations than found in rigid valve designs.

Maximum operating pressure for pinch valves typically ranges from 15 psi for large diameter valves up to 150 psi for smaller sizes with reinforced sleeves. The inverse relationship between valve size and pressure capability stems from basic physics—larger diameter sleeves experience greater hoop stress for a given internal pressure. A 2-inch pinch valve might handle 100-150 psi, while a 12-inch valve of similar construction may be limited to 40-60 psi maximum.

Pressure ratings are specified for sleeves in the fully open position unless otherwise noted. When the valve is partially or fully closed, the effective pressure rating changes because the pinching mechanism adds external stress to the sleeve material. This means the safe operating pressure when throttling may be 20-40% lower than the wide-open rating, a critical consideration often overlooked during valve selection.

Temperature significantly affects pressure capabilities because elastomer properties change with temperature. Most published pressure ratings apply at ambient temperature (68-77°F or 20-25°C). At elevated temperatures, elastomers soften and lose strength, reducing safe operating pressure. Conversely, low temperatures cause stiffening and reduced flexibility, which can also decrease effective pressure ratings. A valve rated for 100 psi at room temperature might only safely handle 60-70 psi at 150°F.

Pressure Rating Specifications by Valve Type and Size

Different pinch valve designs offer varying pressure capabilities based on construction details, sleeve reinforcement, and body support. Understanding these variations helps engineers match valve type to application pressure requirements.

| Valve Size | Open Body Design (psi) | Enclosed Body Design (psi) | Reinforced Sleeve (psi) |

| 1" - 2" | 80 - 100 | 100 - 150 | 150 - 230 |

| 3" - 4" | 60 - 85 | 85 - 115 | 115 - 175 |

| 6" - 8" | 40 - 60 | 60 - 85 | 85 - 130 |

| 10" - 12" | 30 - 45 | 45 - 70 | 70 - 100 |

| 14" - 24" | 15 - 30 | 30 - 50 | 50 - 75 |

Open body pinch valves offer the lowest pressure ratings but provide easiest maintenance access. The exposed sleeve receives minimal external support, limiting pressure capability primarily to the sleeve material strength. These designs excel in low-pressure, high-abrasion applications where frequent sleeve replacement is expected and pressure rarely exceeds 60-80 psi.

Enclosed body pinch valves house the sleeve within a protective casing that provides mechanical support, allowing higher pressure ratings. The rigid body constrains sleeve expansion under internal pressure, distributing stress more evenly across the elastomer. This design suits moderate pressure applications up to 100-150 psi depending on size, making it popular for chemical processing and industrial water systems.

Reinforced sleeves incorporate fabric layers, typically nylon or polyester, embedded within the elastomer. This construction dramatically increases pressure capability, with some reinforced sleeves rated for 200+ psi in smaller sizes. The fabric reinforcement carries hoop stress loads while the elastomer provides chemical resistance and sealing. Multi-ply reinforced sleeves can handle even higher pressures but sacrifice some flexibility and increase cost substantially.

Factors Affecting Pressure Performance

Multiple variables influence actual pressure performance beyond the nominal rating stamped on the valve nameplate. Recognizing these factors prevents pressure-related failures and optimizes valve selection for specific conditions.

Sleeve Material Properties

Different elastomer compounds exhibit vastly different strength characteristics that directly impact pressure ratings. Natural rubber offers excellent flexibility and resilience but moderate pressure capability, typically supporting 60-100 psi in standard configurations. Nitrile rubber provides superior oil resistance with similar pressure ratings. EPDM excels in chemical resistance and can handle slightly higher pressures than natural rubber while maintaining flexibility across wide temperature ranges.

High-performance elastomers like Hypalon, Viton, and polyurethane support higher pressures—often 25-50% greater than natural rubber in equivalent constructions. Polyurethane particularly excels in abrasion resistance and tensile strength, making it ideal for high-pressure slurry applications. However, these materials cost significantly more and may have reduced flexibility or chemical compatibility compared to standard compounds.

Sleeve Wall Thickness

Thicker sleeve walls withstand higher internal pressures through increased material cross-section resisting hoop stress. Standard sleeves typically feature 1/8 to 1/4 inch wall thickness, while heavy-duty sleeves may exceed 3/8 inch for demanding applications. However, increased thickness trades off against flexibility—very thick sleeves require substantially more actuation force to close and may not seal as effectively when pinched.

The optimal wall thickness balances pressure capability, flexibility, and actuation requirements. For high-pressure applications, combining moderate wall thickness with reinforcement layers often provides better performance than simply maximizing thickness. Engineering analysis should evaluate burst pressure, fatigue life under cycling, and pinching force requirements to determine ideal wall thickness for specific operating conditions.

Temperature Effects on Pressure Rating

Temperature influence on pressure performance cannot be overstated. Elastomers lose approximately 2-5% of their tensile strength for every 10°F increase above ambient temperature. A sleeve rated for 100 psi at 70°F may only safely handle 70-80 psi at 150°F. At cryogenic temperatures below -20°F, elastomers become brittle and pressure ratings must be derated by 30-50% to prevent catastrophic cracking.

Temperature cycling introduces additional stress as the sleeve expands and contracts, accelerating fatigue damage. Applications with frequent thermal cycling should use pressure ratings 20-30% below the maximum static rating to ensure adequate fatigue life. Always consult manufacturer temperature-pressure curves that show the relationship between operating temperature and allowable pressure for specific sleeve materials.

Pressure Surge and Shock

Transient pressure spikes from pump starts, valve closures, or other hydraulic shocks can momentarily exceed steady-state ratings. While elastomers exhibit some shock-absorbing capability, repeated pressure surges cause cumulative damage. Systems prone to water hammer or pressure transients should limit steady-state operating pressure to 60-70% of the valve's rated maximum, providing safety margin to accommodate surges.

Installing pressure surge suppressors, slow-closing valves, or accumulator tanks protects pinch valves from damaging transients. For critical applications, pressure monitoring with automatic shutdown at preset limits prevents catastrophic failures. Never rely on the pinch valve itself to absorb or control severe pressure shocks—this dramatically shortens sleeve life and risks sudden failure.

Pressure Drop Across Pinch Valves

Pressure drop represents the energy loss as fluid flows through a pinch valve, affecting system efficiency, pump sizing, and overall operating costs. Unlike inlet pressure rating, pressure drop varies with valve position, flow rate, and fluid properties.

Fully open pinch valves introduce modest pressure drop, typically 2-10 psi at rated flow depending on size and design. The flexible sleeve creates slight flow restriction compared to straight pipe even when not compressed. Open body designs generally produce lower pressure drops than enclosed body valves because the sleeve can expand slightly under flow, increasing effective diameter. For a 4-inch valve flowing 300 GPM of water, expect approximately 3-5 psi pressure drop when fully open.

Pressure drop increases exponentially as the valve throttles toward closed position. At 50% open, pressure drop may be 4-6 times the fully open value. At 75% closed, pressure drop can reach 20-50 psi depending on flow rate. This relationship follows the general valve flow equation where pressure drop is proportional to the square of flow rate and inversely proportional to the valve flow coefficient squared.

Calculating pressure drop requires the valve's flow coefficient (Cv) at the specific opening percentage. The formula ΔP = (Q/Cv)² × SG provides pressure drop in psi, where Q is flow rate in GPM, Cv is the flow coefficient, and SG is specific gravity. For example, with Q = 200 GPM, Cv = 50 (valve 60% open), and SG = 1.0: ΔP = (200/50)² × 1.0 = 16 psi. Manufacturer catalogs provide Cv values versus valve position for accurate calculations.

- Viscous fluids experience higher pressure drops than water at equivalent flow rates due to increased friction losses through the sleeve restriction

- Slurries containing solids produce additional pressure drop beyond that predicted for the carrier fluid alone, often 10-30% higher depending on solids concentration

- Worn sleeves may exhibit reduced pressure drop due to enlarged bore diameter from erosion or stretching, which can serve as an indirect wear indicator

- Temperature affects fluid viscosity and density, indirectly influencing pressure drop calculations for non-water fluids

Vacuum Service and Negative Pressure Capabilities

Pinch valves can operate under vacuum conditions, but performance differs significantly from positive pressure service. Negative pressure causes the flexible sleeve to collapse inward, potentially restricting or completely blocking flow if not properly designed for vacuum applications.

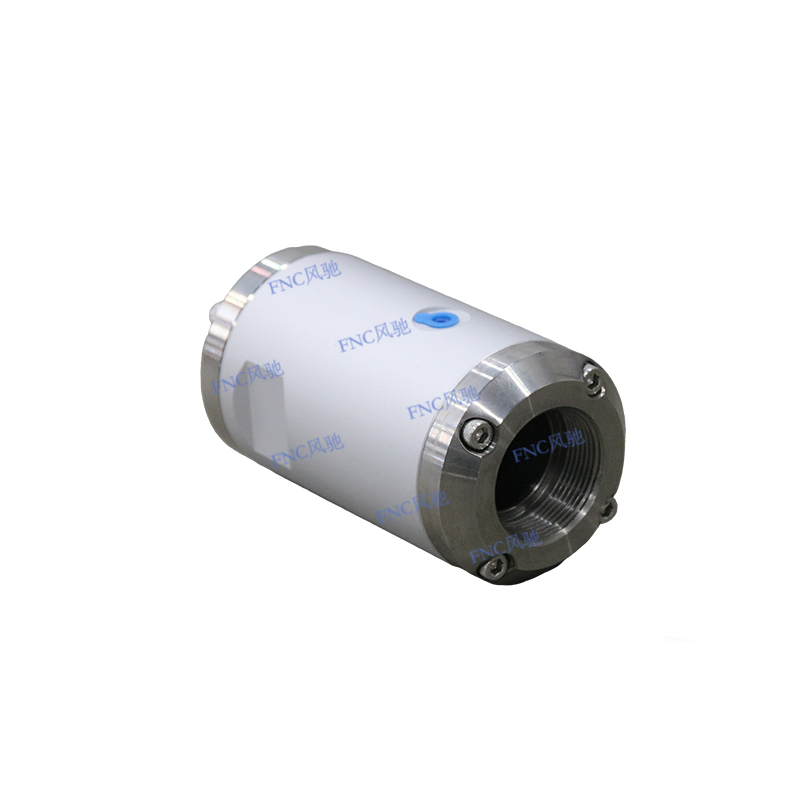

Standard pinch valves typically handle vacuum down to 10-15 inches of mercury (approximately -5 to -7 psi) before significant sleeve collapse occurs. At deeper vacuum levels, the sleeve walls are sucked together, reducing effective flow area and increasing resistance. For applications requiring full vacuum capability approaching 29 inches of mercury, specialized vacuum-rated sleeves with internal support structures are necessary.

Vacuum-rated pinch valve sleeves incorporate wire helix reinforcement or rigid internal ribs that maintain the bore opening under negative pressure. These sleeves function similarly to vacuum hose construction, with the support structure preventing collapse while the elastomer provides sealing and chemical resistance. Vacuum-rated sleeves cost 2-3 times more than standard sleeves but enable reliable operation at full vacuum without flow restriction.

Partial vacuum conditions below 10 inches of mercury generally don't require special vacuum-rated sleeves if flow restriction is acceptable. The sleeve will partially collapse, reducing effective diameter by 10-25% depending on vacuum level and sleeve stiffness. This restriction increases velocity and pressure drop but may be tolerable for intermittent vacuum service or applications where maximum flow isn't critical during vacuum periods.

Combining positive pressure and vacuum service in the same application demands careful analysis. A sleeve optimized for 100 psi positive pressure may perform poorly at even moderate vacuum. Conversely, heavily reinforced vacuum sleeves may have reduced pressure ratings due to stress concentration around support elements. For systems alternating between positive pressure and vacuum, specify sleeves rated for both conditions and verify performance across the full operating envelope.

Pressure Testing and Quality Assurance

Proper pressure testing validates that pinch valves meet specifications and will perform safely in service. Manufacturers conduct various pressure tests during production, and end users should perform acceptance testing before commissioning critical installations.

Hydrostatic Pressure Testing

Standard hydrostatic testing pressurizes the valve sleeve with water to 1.5 times the maximum rated working pressure for a specified duration, typically 30-60 minutes. The sleeve is inspected for leaks, excessive deformation, or other defects. This test confirms structural integrity and identifies manufacturing flaws before the valve enters service. A valve rated for 100 psi should successfully pass hydrostatic testing at 150 psi without leakage or permanent deformation.

Hydrostatic testing is non-destructive when performed correctly but can damage sleeves if test pressure is exceeded or if the sleeve contains trapped air pockets. Air compresses under pressure, creating stress concentrations that can initiate tears. Always vent air completely before pressurizing, and increase pressure gradually at approximately 10 psi per minute to allow stress equalization throughout the elastomer.

Pneumatic Testing Considerations

Pneumatic pressure testing using compressed air or nitrogen is sometimes preferred for field testing or when water contamination must be avoided. However, pneumatic testing carries higher risk because compressed gas stores more energy than incompressible liquids. A catastrophic failure during pneumatic testing releases this energy explosively, potentially causing severe injury.

If pneumatic testing is necessary, limit test pressure to 1.1 times working pressure rather than the 1.5x factor used for hydrostatic testing. Conduct pneumatic tests remotely with personnel behind protective barriers. Consider using nitrogen instead of air to prevent combustion if the sleeve fails at a pinch point where friction could generate sparks. Many safety standards prohibit or severely restrict pneumatic pressure testing of elastomer components due to these hazards.

In-Service Pressure Monitoring

Installing pressure gauges or transmitters upstream and downstream of pinch valves enables continuous monitoring of operating conditions and early detection of problems. Gradual pressure increase upstream or pressure drop increase across the valve may indicate sleeve wear, swelling, or partial blockage. Sudden pressure changes can signal sleeve failure or system upsets requiring immediate attention.

For critical applications, implement automated pressure monitoring with alarm setpoints at 90-95% of maximum rated pressure. Configure shutdown interlocks to close upstream isolation valves or stop pumps if pressure exceeds safe limits. This instrumentation investment protects against overpressure failures that could cause environmental releases, production downtime, or safety incidents.

Pressure-Related Failure Modes and Prevention

Understanding how pinch valves fail under pressure helps implement preventive measures and establish appropriate inspection intervals. Most pressure-related failures develop gradually with warning signs that allow intervention before catastrophic rupture.

Sleeve Ballooning and Deformation

Chronic overpressure causes permanent sleeve expansion, creating a "ballooned" section where the elastomer has stretched beyond its elastic limit. This deformation increases with each pressure cycle, eventually leading to thin spots that fail suddenly. Ballooning typically occurs in open body valves where the sleeve lacks external support, or at connections where the sleeve interfaces with rigid hose or pipe fittings.

Prevention requires maintaining operating pressure below 85% of rated maximum and inspecting sleeves regularly for diameter increases. Measure sleeve outside diameter at multiple locations and compare to original specifications. Permanent expansion exceeding 5-10% indicates the sleeve should be replaced before failure occurs. Reducing operating pressure or upgrading to higher-rated sleeves addresses the root cause.

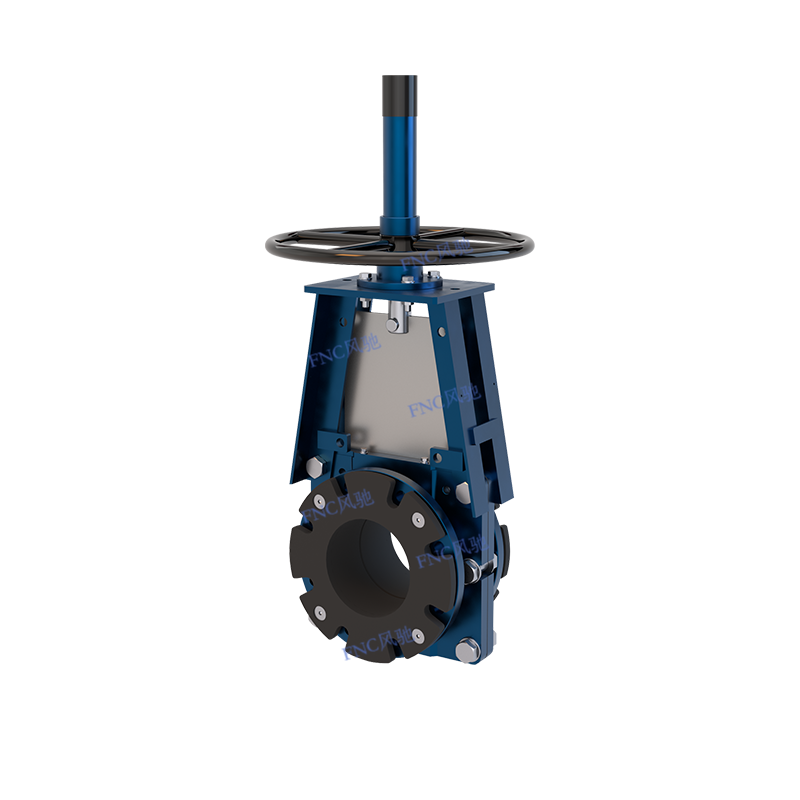

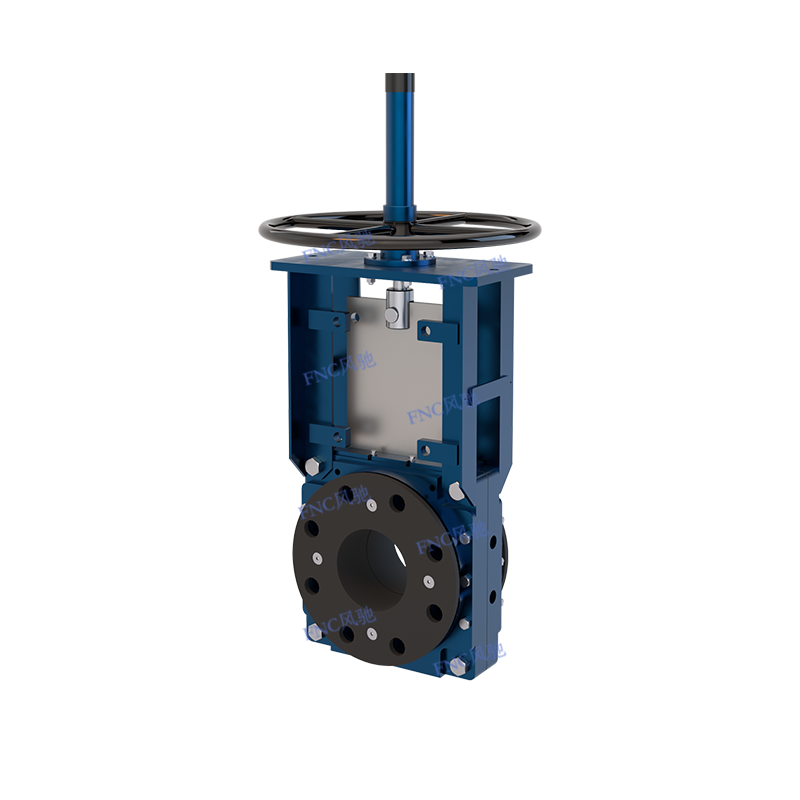

Pinch Point Stress Failures

Operating a pinch valve under high internal pressure while simultaneously pinching to throttle or close creates severe stress concentration at the pinch point. The combined stress from internal pressure plus external compression can exceed material limits even when each stress alone is acceptable. This failure mode appears as circumferential cracks or splits at the pinch location.

Minimize pinch point failures by avoiding throttling operation above 50% of rated pressure. For applications requiring frequent throttling at elevated pressure, select valves rated for at least 1.5 times actual operating pressure to provide adequate safety margin. Alternatively, use dedicated throttling valves upstream or downstream and operate the pinch valve only fully open or fully closed.

Reinforcement Separation

In reinforced sleeves, pressure cycling can cause delamination between elastomer layers and fabric reinforcement. This separation reduces pressure capability and creates bulges where fluids penetrate between layers. The condition worsens progressively as pressure hydraulically jacks the layers further apart with each cycle. Eventually, the unsupported elastomer layer bursts while the fabric remains intact.

Preventing delamination requires proper sleeve manufacturing with adequate bonding between layers, avoiding pressure surges that exceed static pressure rating, and limiting pressure cycling to reasonable frequencies. Sleeves experiencing more than 100,000 pressure cycles should be inspected ultrasonically for internal delamination if possible, or replaced preventively based on cycle count and operating severity.

Optimizing Pressure Performance in System Design

System-level design decisions significantly impact pinch valve pressure performance and longevity. Thoughtful integration prevents pressure-related problems and maximizes return on valve investment.

Install pinch valves in locations where pressure is relatively stable and predictable. Avoid installation immediately downstream of pumps where pressure pulsations are highest. Locating pinch valves at least 10 pipe diameters downstream of pumps or other flow disturbances allows pressure to stabilize and reduces cyclic stress on sleeves. If close coupling is unavoidable, install pulsation dampeners between the pump and pinch valve.

Ensure adequate pipeline support prevents mechanical stress from being transmitted to valve connections. Pinch valves have relatively weak connection points compared to metal valves, and external pipe loads can deform flanges or connections, creating leak paths. Support piping independently on both sides of the valve, and use flexible connections if thermal expansion or vibration is significant.

Consider pressure relief protection for systems where overpressure scenarios are possible. A rupture disc or relief valve set at 95-100% of the pinch valve's maximum rating protects against pump deadheading, thermal expansion in blocked lines, or other overpressure events. This simple protection can prevent costly failures and unplanned shutdowns.

- Implement slow-start procedures for pumps serving pinch valve systems to minimize startup pressure transients

- Install isolation valves upstream and downstream to enable safe depressurization before sleeve replacement or maintenance

- Use pressure gauges with peak-hold capability to identify transient pressure spikes that may not be obvious during normal operation

- Design control systems to prevent simultaneous closure of multiple pinch valves, which could trap and compress fluid causing overpressure

Special Pressure Considerations for Different Applications

Specific industries and applications present unique pressure challenges that require tailored approaches to pinch valve selection and operation.

High-Pressure Slurry Systems

Mining and mineral processing applications often handle abrasive slurries at 50-100 psi or higher. The combination of erosive solids and elevated pressure creates demanding conditions. Reinforced sleeves are essential, but even these wear faster under pressure due to increased particle impact energy. Operating at the lower end of velocity recommendations (6-8 ft/s instead of 10-12 ft/s) reduces erosion rates while maintaining adequate suspension, extending sleeve life at the cost of larger valve sizes.

Select polyurethane or other highly abrasion-resistant elastomers for high-pressure slurry service. These materials typically offer 3-5 times longer service life than natural rubber in these conditions. The higher material cost is offset by reduced replacement frequency and minimized downtime. Some operators successfully use ceramic-filled elastomers that provide even greater abrasion resistance, though these specialty compounds require careful compatibility verification.

Pressure Cycling in Batch Processes

Applications involving repeated pressurization and depressurization cycles—such as filter presses, centrifuge feed systems, or batch reactors—subject sleeves to fatigue stress. Each pressure cycle propagates microscopic cracks that eventually coalesce into visible failures. Sleeves in cyclic service typically last 50,000 to 200,000 cycles depending on pressure range, elastomer compound, and operating temperature.

Extend cycle life by minimizing pressure swing amplitude. If process pressure varies between 20 and 80 psi, the 60 psi swing causes more fatigue damage than constant operation at 80 psi. Maintaining higher minimum pressure or implementing staged depressurization reduces stress reversals. Select elastomers with high tear strength and fatigue resistance, such as premium natural rubber compounds or specialized synthetic rubbers formulated for dynamic applications.

Low-Pressure Gravity Flow Systems

At the opposite extreme, gravity-fed systems operating below 10 psi have different concerns. Low pressure may seem non-threatening, but inadequate pressure can prevent proper valve closing, especially in larger sizes where sleeve weight is significant. A 12-inch valve sleeve may require 5-10 psi minimum internal pressure to fully inflate and seat against the pinch mechanism for complete shutoff.

Verify minimum pressure requirements with manufacturers for large valves in gravity service. In some cases, slightly pressurizing the system with compressed air or installing the valve with a modest elevation head ensures adequate closing pressure. Alternatively, specify thinner-walled sleeves that require less inflation pressure, though this reduces maximum pressure capability if the system ever transitions to pressurized operation.

Pressure Rating Documentation and Compliance

Proper documentation of pressure ratings and operating limits ensures regulatory compliance and provides essential information for safe operation and maintenance. Pinch valve pressure documentation should include specific details beyond simple maximum pressure numbers.

Manufacturer nameplates or documentation should clearly state maximum working pressure, test pressure, temperature range for rated pressure, and applicable standards or codes. For example: "Max Working Pressure: 100 psi @ 70°F, Hydrostatic Test: 150 psi, Rated Temp Range: 32-150°F, ASTM D2000 Compliant." This information enables operators and maintenance personnel to verify that operating conditions remain within safe limits.

Pressure vessel codes such as ASME Section VIII may apply to pinch valves in certain jurisdictions or applications, particularly for larger sizes or hazardous services. While most pinch valve sleeves fall below the size and pressure thresholds requiring code certification, always verify local regulations. Some industries like pharmaceuticals or nuclear have specific documentation requirements regardless of pressure level.

Maintain records of all pressure testing, both initial factory tests and any field testing performed during commissioning or maintenance. Document actual operating pressures periodically to demonstrate compliance with design limits. For critical applications, establish a pressure monitoring log that tracks maximum, minimum, and average pressures weekly or monthly, enabling trend analysis to identify degradation or process changes before they cause failures.

Replacement sleeves should be documented with batch numbers, installation dates, and removal dates to track service life and identify performance patterns. If certain sleeve batches or materials demonstrate superior pressure performance, this information guides future procurement. Conversely, premature failures can be traced to specific manufacturing lots or material formulations, enabling targeted quality improvements with suppliers.

EN

EN

English

English русский

русский Español

Español